CHAPTER 7 - WWII JAPANESE MILITARY TACTICS - section 2

1. ORGANIZATION FOR DEFENSE.

a. General.

(1) Object.

The object of the defensive as visualized by the Japanese does not differ in principle from that of other armies. The Japanese seek to suplement inferiority in strength by the utilization of such material advantages as the terrain, fortifications, and thorough preparations for combat, and to break up hostile attacks by the combined use of fire power and counterattacks.

(2) Japanese attitude.

The very word "defense" is distasteful to the Japanese, and is contrary to the Bushido (warrior) spirit with which the Japanese soldier has been imbued since childhood. When forced on the defensive, therefore, he is at all times preparing and planning counter attacks to break up the enemy's assaults and so regain teh initiative. The Japanese first counter attack in force; if such attacks fail they commence fanatical, suicidal, small scale attacks. These are supplemented by many small infiltration operations. When all such efforts fail, they will defend, literally, to the last man.

Each sector commander is responsible for the construction of defenses and the general defense of his area in accordance with the main plan.

In taking up their positions, the Japanese lose no time in digging in and making their respective sectors in strongpoints. Reconnaissance of some of their positions has shown the usual priority of tasks to be as follows:

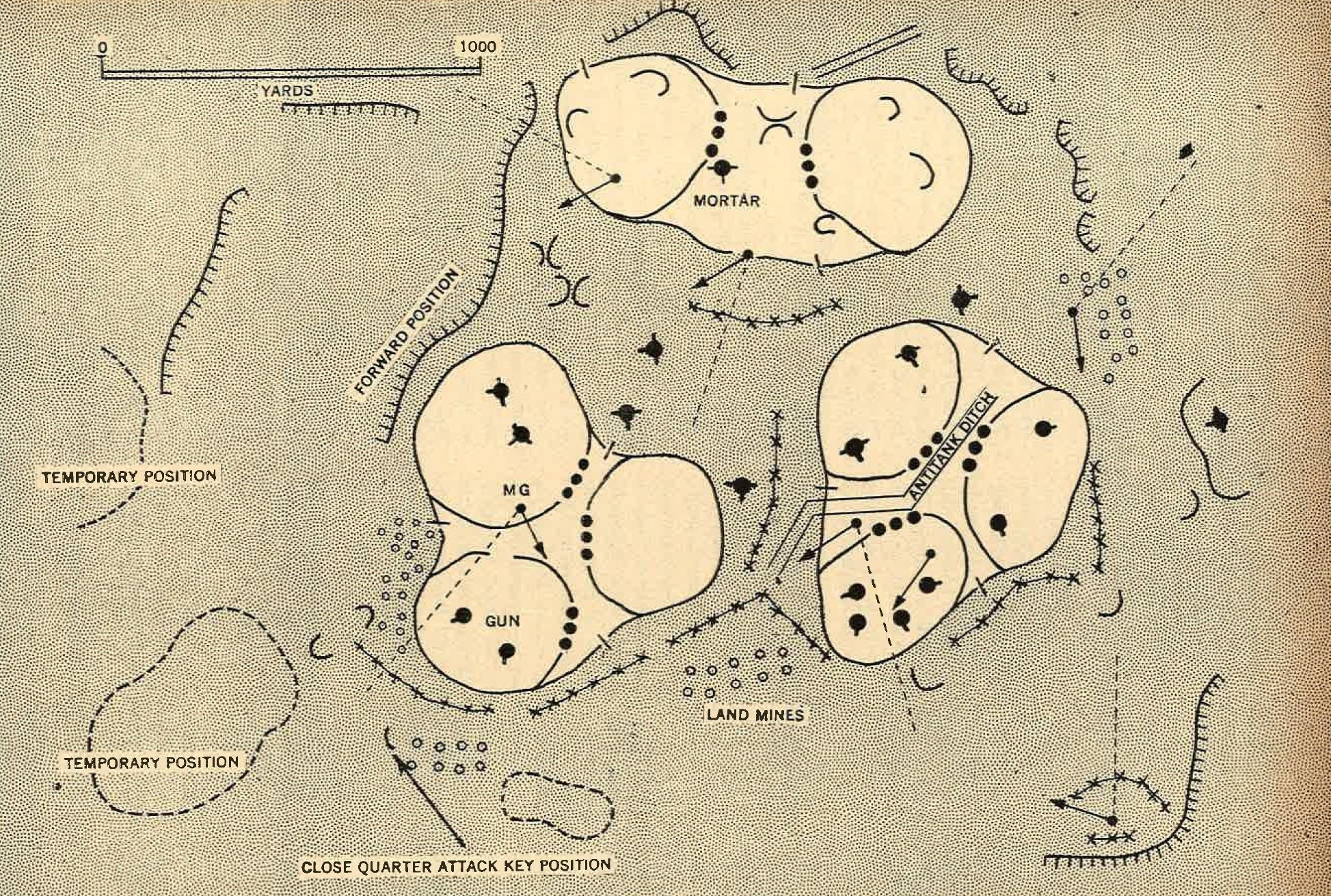

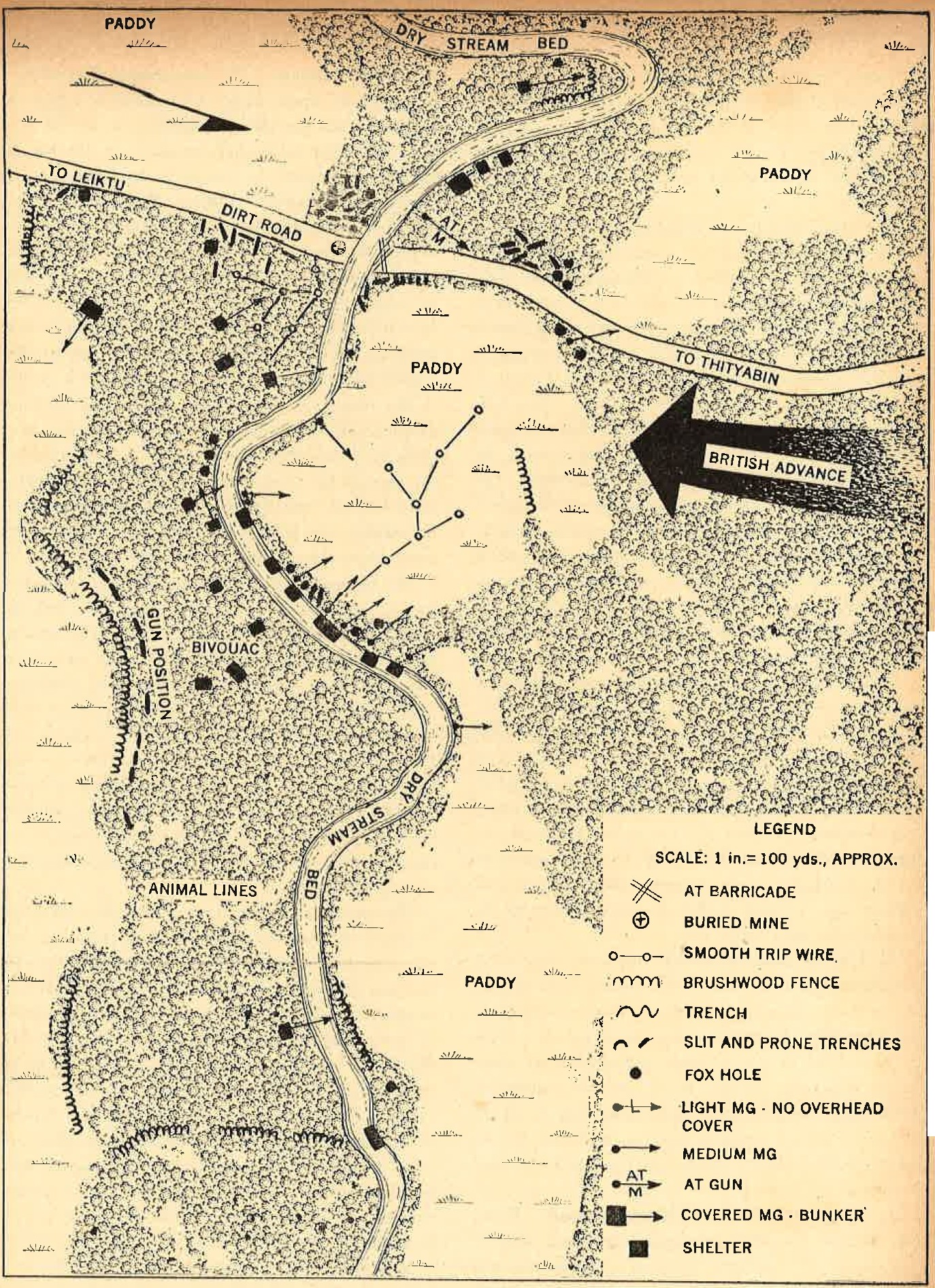

The whole Japanese defense position will be built to give protection from tanks. If there are no natural obstacles to the front or flanks, tank ditches may be dug, or narrow streams may be widened and deepened to make them effective obstacles. Gaps between these obstacles are mined and covered by fire. The mines very frequently are boosted by placing artillery shells beneath them. Likely roads of approach to the position will probably be blocked and mined. These road blocks may take the form of formidable cement structures or merely felled trees.

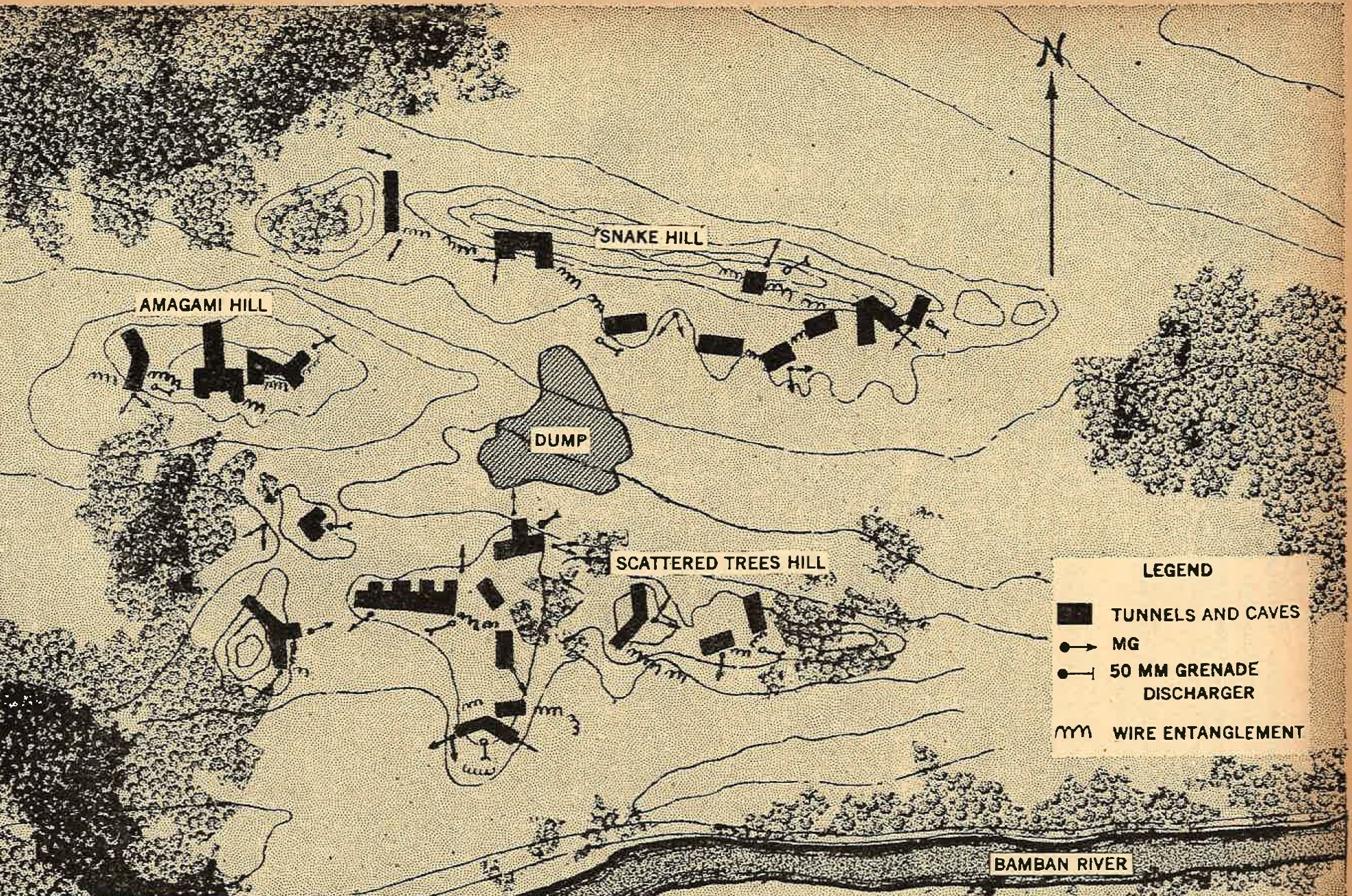

Great stress is laid on camouflage and concealment. In addition to the normal precautions taken to blend guns, pillboxes, and fox holes into the natural background of the terrain, tunnels frequently will be dug between pillboxes and various unit headquarters. Natural caves will be utilized whenever they are in the vicinity. These will be improved by tunnels and additional ports, by enlarging shelter caverns, and by camouflage. All cave positions will be tied in with needed surface fortifications such as pillboxes and fox holes, and the entire system will constitute a most effective area for defense.

When the main Japanese position is built on a reverse slope, observation posts and patrols initially willbe placed on the summit and forward slopes. As the position is developed, pillboxes are constructed on the forward slopes as well.

Where there is no commanding ground, the Japanese center their defenses around native villages, digging in usually in the bordering hedges, under trees, or in thick bamboo clumps. Such positions have proved effectively obstacles to our tanks. The frontage for a battalion in defense naturally depends on teh type of terrain; it has varied from 800 to 5,000 yards. A Japanese document gives the normal battalion frontage as 1,500 to 2,000 yards with a depth of 1,000 yards.

d. Outpost positions.

The outpost position ( Keikai Jinchi ) is set up in front of each sector to observe the enemy's approach, slow his advance, and attempt to anticipate his plans of attack. Its disposition depends upon the terrain, but it is generally from 1,500 to 3,000 yards in from of the main line of resistance, so as to be within supporting range of light artillery. The Japanese rarely developed an intricate outpost defensive system, but invariably select commanding ground where they may observe most effectively the enemy's approach and make the best use of their limited fire power. The strength of the outpost position varies with the mission ordered by the main force commander, but the Japanese prescribe that it will be no stronger than absolutely necessary. They aldo emphasize that the outpost positions must not form a continuos line. Isolated cases have been noted where they have eliminated outpost positions entirely. This probably has been attributed to a paucity of troops, and has been done where the defense commander considered small reconnaissance patrols adequate.

e. Advanced defensive positions.

In addition to his outpost positions, the Japanese defense commander may order the occupation and organization of an advanced defensive position ( Zenshin Jinchi ) between the outpost and main positions . Its purposes are to prevent, for as long as possible, the occupation by hostile forces of critical points of terrain near the main defensive zone; to delay the enemy's preparations for an attack; and to induce him to launch his attack in a false direction. The setting up of such positions, which include machine guns and antitank weapons, is not coomon Japanese practice. Typical cases where they have been encountered are:

(1) where, in order to obtain observation, the outposts have been pushed well forward, leaving an important ridge in the foreground of the main position ungarrisoned;

(2) Where an oblique position is organized between the outpost and main positions, with one flank resting on the outpost line of resistance, while the other rests on the main line of resistance, thus inducing the enemy to expose a flank.

f. Reserves, artillery, command posts.

(1) Reserves.

The present Japanese trend indicates that they are holding a larger proportion of their defense forces in reserve than therefore, quite in accordance with their doctrine of aggressive defense. In some cases, they have been known to hold almost a half of their strength in readiness for the counter attack. Troops held for counter attack are disposed behind the main infantry line, usually in shelters and tunnels which are protection against the heaviest artillery and air bombardments. Their exact location will be dependent on the nature of the terrain and the battle situation. Tanks will usually be attached to the reserve force.

(2) Artillery.

Japanese guns will normally be dispersed behind the infantry main line. Usually sinlgy, sometimes in pairs. They are housed in well camouflaged emplacements or pillboxes disposed in depth. Some of the pieces may be sited well forward in the main position in order to support the outpost troops. Many alternate emplacements will be prepared in readiness for moving the guns when it is considered that they have been spotted.

(3) Command posts.

These generally are established in well sheltered positions in rear of the main line of resistance; that of the division is usually located at a distance of about 5,500 yards, that of the infantry group 2,700 yards, and that of the infantry regiment at about 1,300 yards in rear of the main line of resistance.

2. CONDUCT OF THE DEFENSE.

a. Defense of the outpost positions.

Troops of the various sector outpost positions are the first to observe and come in direct contact with the attacker. In their mission to delay the attack, defenders of outpost positions will be send out small fighting patrols to harass the enemy. Artillery support will be given by guns situated in the main position. The degree of resistance by troops in outpost positions depends upon the particular nature of their mission. Sometimes they are ordered to defend their positions to the last man in order to delay the attack as long as possible. More frequently, however, when it becomes apparent that they no longer can hold off the attackers, they will withdraw. This withdrawl is made along previously reconnoitered routes, and is often planned to lead the attackers into a trap where they will expose a flank.

b. Defense of the advanced position.

The actions of the advanced position will follow closely that of the outpost position. It will invariably withdraw, however, when it can no longer hold up the attack. Clear orders are issued by the main defense commander specifying the time and routes of withdrawl and giving new missions for the force when it reaches the main position.

c. Defense of the main battle position.

One of the most difficult tasks of a force attacking a Japanese position is to locate that position. The enemy's skill in remaining concealed and observing absolute silence has on many occassions given him the element od surprise necessary for countering an attack.

When, however, the Japanese realize that their position has been spotted, and an attack is inevitable, hey brng down artillery and mortar fire in the area where the hostile infantry is forming. The Japanese do not make the maximum use of these weapons by massing the fire, but put it down sporadically. They will frequently fire at the same time as do hostile guns, placing the shells on the enemy's forward advancing infantry. Their intention is to demoralize hostile troops by giving them the impression that their artillery rounds are short ranged.

Japanese commanders send out patrols - chiefly of the suicide type - to harass the attacker and to attempt to break up his plan of attack. These suicide patrols, although their mission usually precludes their return, are not just thrown away. They use every ddevice to cause the maximum number of casualties among hostile leaders, and to destroy as many installations as possible before they themselves are killed. One common mission of such patrols is the destruction of artillery pieces which are causing them trouble.

Japanese snipers are placed forward to provide a protective screen. The snipers usually do not make a stand, but attempt to disorganize the attack and then withdraw. They are always well camouflaged and take up concealed positions in bushes or up trees. On occassion, they do not open fire on the first wave of attack but remain concealed until targets are offered in the rear of the first or in the second wave.

As the hostile force advances to the main line, Japanese troops will first defend by small arms fire and later with the bayonet. as one strong point is occupied, fire and bayonet charges may be exposed from neighboring strongpoints on the flanks or rear of the attacker. Mortar fire will be brought to bear on teh position; any Japanese troops thre at the time will go to their tunnels or hide in pillboxes awaiting their chance to counter attack. Parties will come from the rear, attempting to infiltrate and reoccupy positions.

The Japanese will fight tenaciously as their positions are taken. They will not diw always in their strongpoints, if they consider that, by moving to positions in the rear, they have chance of regaining the initiative. Troops in cave areas, however, often have died in their positions because orders to do so have been given them, or because their means of escape have been blocked too soon.

d. Counterattack.

Japanese doctrine dictates that when an enemy penetrates the defense position, a swift daring counterattack must be launched, and their operations thus far have revealed that they practice this. It must be borne in mind, however, that these counter attacks are not merely disorganized assaults. Defense commanders invariably prepare several plans to meet likely breakthroughs by the hostile force. In one large scale defensive operation, seven separate counter attack plans had been devised.

These counter attacks normally follow the form of the accepted Japanese offensive plan. The main line infantry engages and attempts to hold the hostile push, while detachments from the reserve are sent around to one of both of the enemy's flanks in an encircling movement. at the same time, small infiltration parties are sent out. The encircling force is to cut the attacking force in two; while infiltrating parties make suicide attacks on tanks, vehicles, guns, and headquarters.

Tanks may be employed, usually singly, as mobile pillboxes; the Japanese rarely use then to counter our tanks. In addition, artillery and mortars will be employed to support the forward advance of the counterattacking troops.

3. COMMENTS.

Although the recent trend of event has forced the Japanese into all out defensive, they by no means have lost their aggressive attitude, and it is on the attitude that they base their normal defensive operation.

Japanese small unit defensive tactics are good. They are adept at digging themselves in and putting a position in a state of defense in an incredibly short time. It is questionable, therefore, whether the term "attack of a hastily prepared position" is ever applicable against the Japanese. It should be remembered by the attacking force that the longer attack is delayed, the more difficult it will be to dislodge the Japanese who are constantly improving their positions.

There is no doubt that the majority of positions contain far more defenses than the defending force can possibly man. This permits greater maneuver within the position and tends to give the attacker an impression of greater strength than actually exists.

The main fault of the Japanese defensive appears to be in the execution of large scale operations whicj lack thorough coordinated planning. Small units defend their strongpoints tenaciously, launching frequent daring counterattacks which inflict substantial casualties. Large scale counterattacks have been launched when the situation permitted, but the results obtained from them have not been commesurate with the men and materiel expended.

1. THE WITHDRAWL.

a. GENERAL.

No information has been obtained as to when a Japanese commander considers a withdrawl required or justified, but experience indicates that he will rarely whithdraw unless such a movement gives him a tactical advantage in his current operation. The general principles followed are similar to our own, except that the Japanese appear to have little objection to a daylight withdrawl.

b. Preparations.

The Japanese division commander, in anticipation of a withdrawl, first attempts to clear his rear area of supply troops and installations, improves the roads which he expects to use, and orders preparations for demolitions to delay the enemy pursuit. All preparations are made with the utmost secrecy while preserving a bold front.

c. Execution by day.

Breaking of contact by the front line infantry is done under the protection of local covering forces, disposed from 1,500 to 2,000 yards behind the firing line. These troops are obtained from battalion, regiment, or other reserves not committed to the front line fighting. The position occupied is, when possible, to the flank of the line of retreat on commanding ground that permits overhead fire in support of the retiring troops. The local covering forces give support by fire and, on occassions, may launch a counterattack. Size of the local covering force varies with the strength of the terrain on which it is to defend, but it appears to be only a small percentage of the total unit.

In addition to these local detachments, the division commander organizes a general covering force ( shuyo jinchitai ) behind which he reforms the major elements of his command. The division reserve is usually the main component of this covering force which, in principle, is made up of the freshest troops available. The bulk of the division artillery withdraws and deploys behind this covering position to protect the withdrawl. The Japanese try to place the covering position at an oblique angle to teh axis of retreat and from 3,000 to 5,000 yards in rear of the front line. The division command post is set up behind the covering position for the purpose of controlling the withdrawl and organizing the subsequent retirement for which the troops on the covering position eventually become the rear guard.

Protected by the covering forces, the front line infantry withdraws straight to the rear. The Japanese feel that it is desirable for all front line units to pull back simultaneously, but often some must hold on longer than others. The division artillery, the bulk of which has already retired to the general covering position, supports the withdrawl. In some sectors, a local counter attack amy be launched in an attempt to hide the withdrawl intention. Retreating units reform progressively, arriving by many small columns in the general assenbly area behind the general covering position. Here, division march columns are formed and directed toward the final terrain objective of the withdrawl. The engineers execute demolitions; mines are laid and special attention is paid to the setting of booby traps. Precautions are taken to prevent turning movements around the flanks by enemy pursuit detachments.

d, Execution by night.

The night withdrawl differs from that in daylight in the following important respects:

(1) The local covering mission is performed by a "shell" of small detachments left in position on the front line throughout most of the hours of darkness.

(2) Retiring units reassemble and form march columns nearer the front line than is the case in daylight.

(3) A general covering position is not normally organized. Detailed preparation in daylight is necessary prior to a night withdrawl.

The breaking of contact by the front line infantry is done under the cover of a thin line of infantry detachments, strong in machine guns and supported by a small amount of artillery. This "shell" simulates the usual sector activity throughout the night to deceive the enemy and, if attacked, sacrifices itself in its position to protect the retirement. Its time of withdrawl, usually about dawn, is set by the division commander. The mission of the "shell" may be facilitated by local attacks executed early in the night by front line detachments prior to their withdrawl. A small general covering force, strong in cavalry and mobile troops, may be organized to get the "shell" away without undue losses.

In action of the front line units is essentially the same as in daylight, except that the assembly areas are farther forward.

e. march plan.

Details of a typical Japanese infantry march plan, which required a mixed force to cover approximately 13 miles a night, were contained in a Japanese order for a withdrawl along the jungle coast of northeastern New Guinea. The forces was one of three from a single division which were involved in the movement. According to the plan, the force was to march from 2000 to 0400 hours on successive nights until it reached its destination, 50 miles away. The order warned that if any hostile activity occurred, it probably would consist of landings on the coast. Communications, security, bivouac, and care of the weak and wounded were some of the problems dealt with in the order.

The force consisted of the follwing units:

- Part of division headquarters.

- Infantry battalion less two rifle comnpanies.

- Battery of mountain artillery.

- Company of engineers.

- One wire and one radio signal section.

- Military polkice detachment.

- Medical detachment.

- Litter bearer platoon.

The force was divided into three groups to facilitate the march and to diminish vulnerability to air attack. Each group, organized to fight independently, was instructed to attack immediately in case of a hostile amphibious attack. However, the group commanders were instructed to combine their strength, if possible, in the event contact was made with the enemy.

Communications between the three groups were to be maintained by runners. Each group was ordered to detail a noncommissioned officer and two orderlies to the force headquarters to receive and relay messaegs. The group commanders were required to report their position, bivouac areas, and the next day's route data by 1,000 hours every day, and the force commander was to furnish similar information to the division commander.

Sich and weak soldiers were to be hospitalized or sent ahead of the march column. During the movement, medical examinations were to be made independently by each group.

Unless weather, terrain, or unexpected hostile action made it necessary to alter the plan, the force was to march for 8 hours and be at a bivouac area and ready to take cover by dawn. During the day, until 1800 hours, the troops were to keep under cover, rest, and make preparations for cooking. The 2 huors from 1800 to 2000 hours were assigned for cooking the evening meal and also enough food to last until the next cooking period the following evening.

The rate of march was set at 1 1/4 miels per 30 minutes, followed by 15 minutes rest. INtervals were fixed at 55 yards between units, and at six tenths of a mile between the three groups into which the march column was divided. In order to maintain a uniform pace, proper intervals, and the time schedule, officers were cautioned to keep firm control of their units, to use connecting ropes, and to maintain contact by use of panels and other visual signaling.

All personnel were cautioned to watch the sea closely during the march - sepcially at night - and to be prepared at all times to meet any unexpected hostile action from the direction. To ensure secrecy of movement, native villagers were to be avoided, and certain precautions were to be observed in making camps. Bivouac areas were to be situated in suitable cover and camouflaged, and were to be no closer to a village, road, or beach than 325 to 450 yards. Tents were to be pitched 30 to 55 yards apart. Fires were prohibited during the day, and the troops were forbidden to walk on roads and beaches and in villages during daylight.

f. Comment.

The chief criticism of the Japanese in the withdrawl is not in the manner in which they carry out an organized and well planned withdrawl, but in their failure to appreciate the value of such an operation. Instances have occurred where they have thrown away hundreds of troops in a futile attempt to hold positions to the last man, when, by carrying out an organized withdrawl, they could have moved to positions in their rear and reinforced other units. This failure is no doubt the result of the Japanese dislike of any retrograde movement and their over emphasis on attack.

Even in the planned withdrawl the note of aggressiveness is ever present. When a Japanese commander initiates a withdrawl he expects to return over that same ground in his ultimate counterattack. If he cannot take his guns with him during the withdrawl he tries to bury them ready for the counteroffensive.

Decentralization of command and the practice of leaving samll unit commanders without any specific orders have tended, in some cases, to make a Japanese withdrawl almost a rout. There is no doubt that these cases will continue until the Japanese realize the value of the withdrawl and become better trained in its execution.

2. DELAYING ACTION.

a. General.

The Japanese do not recognize the delaying action as a separate and distinct form of military operation, but include it in the broader term jikyusen (holding out combat). This expression is used to cover, in addition to pure delay, a number of types of operations characterized by a desire to avoid a fight to a finish, but in which the idea of delay is somewhat remote. Thus, in addition to the typical delay situations, such as the action of rear guards and covering forces, the Japanese treat under jikyusen demonstrations, reconnaissance in force, and night attacks designed to cover a withdrawl.

c. Conduct of the delaying action.

When the decision has been reached to delay anadvanceing enemy, the Japanese division commander sends out his cavalry to establish and maintain contact and to initiate the delaying action within limits of its combat capacity. He then selects the position or positions upon which he expects to gain the required time for the accomplishment of his mission. He often will send forward an infantry detachment, of from two companies to a battalion, to occupy an advanced position ahead of the first delaying position. Such an advanced position is located within range of artillery support from the delaying position in accordance with the principles for choosing an outpost line of resistance. These forward troops assist the cavalry, as the latter falls back to the flanks of the delaying position, and impose some loss of time on the advancing enemy.

The enemy is taken under fire by the Japanese division artillery at extreme ranges. Artillery positions are close behind the infantry, grouped together for ease in fire direction in the belief that there is little to fear initially from hostile counterbattery. Eventually, the infantry machine guns join in the fire fight as the enemy comes within range.

The Japanese division commander makes every effort to hold out a large reserve. In cases noted, this amounted to from a third to a half of his infantry and a battalion of artillery. The main purpose of this large reserve is not to counterattack (although saome of it on accasion may engage in local offensive action) but to reconnoiter, rpepare, and occupy the next delaying position from which it covers the withdrawl if the troops of the first position.

The Japanses thus contemplate, in effect, delay on successive positions occupied simultaneously, although this form of action is implied rather than clearly defined.

The engineers of the division find their principal missions in road maintenance, route marking, and the preparation and execution of demolitions. The last are carefully planned to cover the flanks and routes of direct approach to the delaying positions. as in oher forms of cpmbat, the Japanese count heavily on measures of deception to assist in accomplishing the delaying mission. Devices used to create this deception are:

- Dummy engineer works.

- Demonstrations.

- Economy of force in wooded and covered areas while strength is displayed in open terrain.

- Roving artillery.

- Proclamations.

- Propaganda.

All these measures aim to create an impression of strength which will cause the enemy to adopt a cautious attitude toward the delaying force. In spite of the fact that such measures impose fatigue on the troops and, in extreme cases, may lead to a serious dispersion of effort, the Japanese feel their use is justofied.

Japanese troops on the delaying positions retire on order of the division commander while the enemy is still at a distance, unless the mission specifically requires a long delay on a single position. When the hostile infantry arrives within 1,000 yards of the position, withdrawal is begun, while troops on the next delaying position provide covering fire. Detachments left in the zone between the positions effect intermediate delay. WHen it has not been possible to prepare and man a second position, the division commander tries to put off his withdrawal until nightfall.

d. Comments.

As a defensive form of combat the delaying action does not appeal to the Japanese soldier who thinks first and last of fixing bayonets and moving forward. Influenced by the strength and weakness of this psychology, the Japanese commander often will choose offensive action when the defensive is better suited to the immediate situation. It has been noted that a little fresh encouragement has been given in the new Japanese field service regulations to the use of offensive action to obtain delay, an encouragement of which Japanese commanders can be expected to take full advantage in order to seek delay through attack. It is felt that this over aggressiveness may ill serve the usual purpose of delay.

The injuction to hold out a large reserve does not agree with the usual teachings on delay. A reserve suggests the intention to counterattack, whereas a delaying position usually is abandoned before the enemy has come within counterattacking range. In the practice of map problems, this large reserve was always used to occupy a rear delaying position, so that the operation became, in effect, a delay on successive positions simultaneously occupied. Thus, the requirement of holding out a large reserve, in spite of its apparent contradiction, becomes reconciled with orthodox tactics.

The Japanese dislike for using their light artillery at long ranges tends to keep successive delaying positions relatively close together (2,000 - 4,000 yards). It is generally considered that 5,500 yards is the extreme limit of effective ground observation, and it is rare to assign missions beyond that range. Japanese artillery has had little experience in fire with air observation.

Despite this failing, it is reasonable to suppose that the Japanese have learned the latest methods of withdrawal as employed by modern armies which place great emphasis on the use of tanks, mobile artillery, motorized infantry, mines, tank traps, aircraft, amd a new concept of distance.

1. EMPLOYMENT IN MASS.

Although few large commitments of Japanese tanks have occurred so far outside the Chinese theater, their army tank school gives precise instructions for the employment of large armored formations. For an attack on a lightly held enemy position Japanese doctrine maintains that a minimum of 30 to 40 tanks are required. If the enemy is in a strongly defended position it is stated that at least 60 will be needed, and this number should be increased to 100 when hostile shelling and bombing are unusually heavy. These mass attacks, say the Japanese, should be directed against weak spots in the opposing lines. There is reason to believe that when they launch such mass attacks they will employ envelopment maneuvers,so favored in their infantry doctrine.

2. INFANTRY SUPPORT.

a. Methods and objectives.

One of the chief factors governing the tactics of tanks is the comparative lightness of their armor and armament. Becasuse of this and their lack of air superiority, tanks are normally employed at night. They are used in small groups of four to six tanks, sometimes even two. One of their main missions has been in support of infantry in attacks on defended perimeters. They have also been used to support infantry in attacks on road blocks.

These attacks sometimes follwo a heavy artillery barrage. On one occassion, five tanks were attached to a small task force containing all arms with the mission of following an Allied withdrawal. At the same time, the main Japanese attacking force attempted a wide outflanking movement.

b. Division attack.

Tank attacks of division strength, according to Japanese manuals, will have a front of about 2,700 yards and will employ three tank regiments with a total of approximately 135 tanks. The tanks are committed in three echelons. Two infantry regiments are deployed in the front line, with one tank company deployed considerably in advance of each of them. The mission of the first tank echelon is to neutralize enemy antitank weapons and strongpoints to clear a path for the second echelon.

The latter is deployed immediately in front of the main body of assault infantry, usually with one tank company in front of each of four infantry battalions. The tanks move about 400 to 500 yards behind the first echelon, covering the infantry and paying special attention to hostile automatic weapons. If the situation demands such a course the second echelon may leapfrog the first. The third, or reserve, echelon is used for exploitation or reinforcement of such second echelon units as may require aid.

c. Close support of infantry.

When the support of the infantry by the tanks must be exceptionally close, the tanks are allocated to two combat units. The first combat unit is divided into left and right formations, each of which is preceeded by a patrol of light tanks to locate the hostile position and draw the fire of antitank weapons. Both the formation of the first combat unit consists of four tank platoons, drawn up in two columns of equal strength.

The two forward platoons advance with the infantry, while the two rear platoons swing around the flanks to engage enemy antitank weapons as their location is disclosed. The second combat unit consists of two platoons assigned to liquidate hostile automatic weapons that survive the first echelon. The unit also holds a reserve to provide reinforcements or to exploit success.

3. TANK-VERSUS-TANK OPERATIONS.

The Japanese, so far, have avoided, whenever possible, a clash with Allied tanks, although their doctrine states that the tank is the only ground weapon fully capable of dealing with tanks. One of the few such engagements occurred in Burma when British tanks made contact with the Japanese in a jungle clearing. Six British Lee tanks, three Bren armored carriers, and one company of infantry were ambushed by seven Japanese light tanks and supporting infantry concealed at the edge of the clearing.

As the first Lee tank approached, the Japanese tanks opened up at almost point blank range, knocking out one of the British tanks. The remaining Lees were ordered to move behind the enemy positions. Thereupon, the Japanese tanks tried to pull out and virtually charged the Lees which were blocking their line of withdrawal. Four of the enemy tanks were knocked out by 75-mm and 37-mm fire; one was captured practically intact, and the other two escaped.

4. TANKS ON THE DEFFENSIVE.

In defense the Japanese normally employ tanks to remedy their deficiency in antitank guns and to strengthten the firepower of their infantry. They appear to have little conception of mobile defense or of the use of tanks for immediate or deliberate counterattack. On occasions the tanks have been dug in and became nothing more than pillboxes. In a few cases they have been employed to strengthen the fire power of a light infantry screen covering a withdrawal.

5. COMMENT.

In general, both offensive and defensive employment of Japanese armor has lacked initiative, and losses out of all proportion to results obtained have been incurred. In some cases, the medthods of employment are forced upon the Japanese bu the lightness of their tank armoe. They are aware of these defects, and future developments may permit them to deploy tanks in a more orthodox manner.

1. GENERAL.

Although the Japanese themselves have not used tanks extensively they are fully aware of the effectiveness of armor in the attack, and have developed their antitank warfare to a high level. Protection against tanks is a keynote of their whole defensive system. The apparent shortage of antitank artillery in their formations has forced them to improvise and put into use many unorthodox tactics. These methods they combine with normal antitank activity.

2. ANTITANK MINES.

Where Allied units are known to have tanks, the laying of mines is considered the most essential duty of the Japanese divisional engineer regiment. In one particular operation involving a division it is known that 12,000 mines were laid. Past use of mines by the enemy has shown that they are most likely to be used in the following places:

a. Beaches.

Mines are used on beaches in one or more of the following cases:

- That section of the beach lying between high tide and low tide levels.

- At the edge of high tide level.

- The area from 25 to 30 yards inalns.

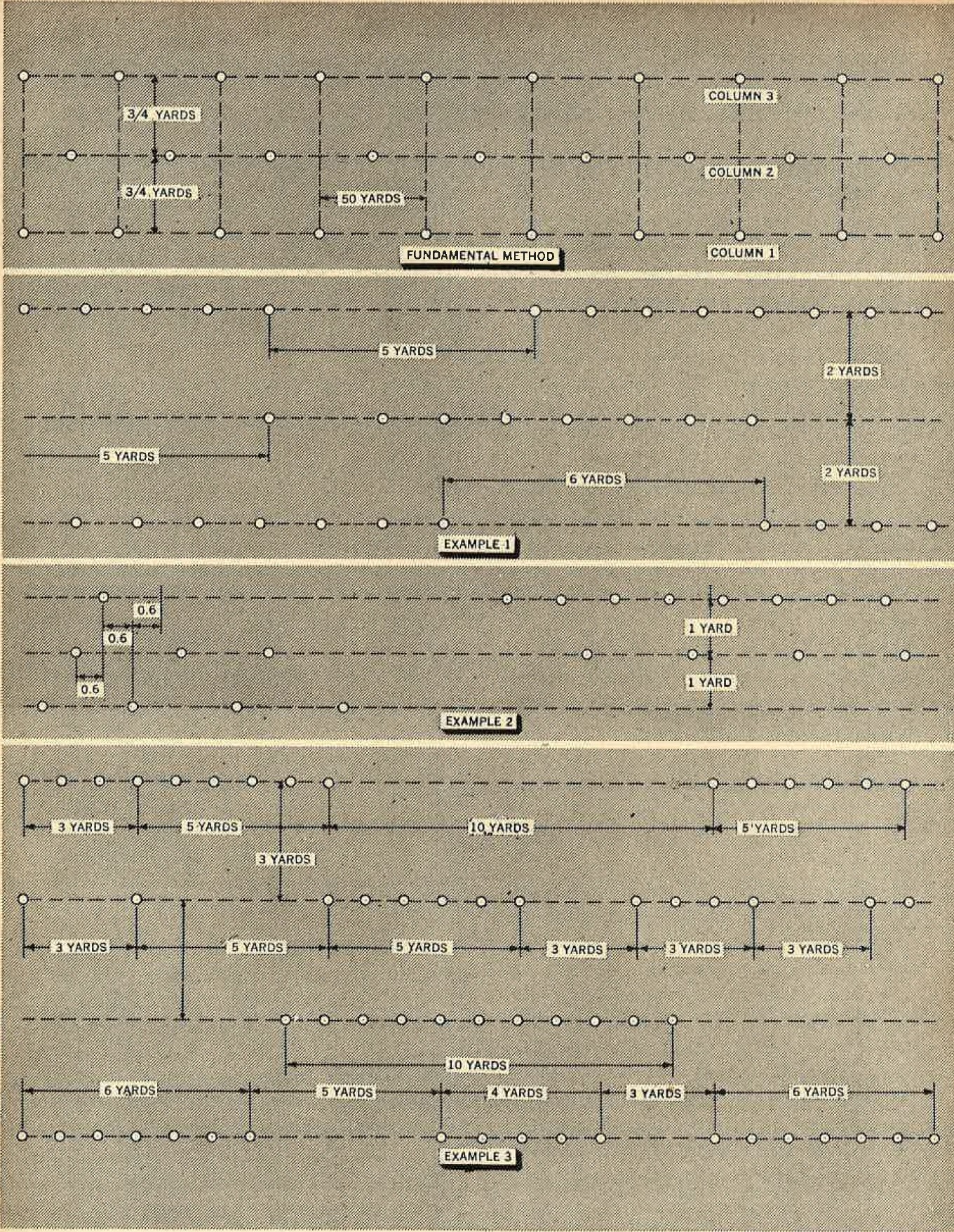

Usually mines are laid in rows, with rows from a few feet to 10 yards between them. Individual mines in a particular row may be spaced from 10 to 30 feet apart.

b. Open fields.

Mines are frequently found in large open fields or in the area that may be termed the approaches to the field. Their employment in most cases is the same as employed inland from the beach. They will be placed in rows, and the mines may be expected to be spaced regularly in the row.

c. Roads.

Ordinarily, junctions of roads and approaches to bridges will be most frequently mined. Special care should be exercised to ensure that shoulders of each road are free from mines before the road is used extensively.

d. Cities.

The cities taken by the Allies have yielded many Japanese mines. The location seems to follow the general rule applied to mines found along roads. More mines were found in the centerof the city streets than on open roads; street intersections and shoulders were frequently mined. Entrances leading into official buildings and parks were also mined.

e. Pillboxes.

Because of the characteristics of pillboxes their field of fire is necessarily limited. Therefore, land mines are sometimes used to cover the approaches bordering the field of fire from a pillbox.

f. Approached to obstacles.

Approached to antitank barricades and detours around them are likely to be mined and covered with fire from neighboring positions.

g. Methods of laying.

The mine either is laid on top of the ground or buried so that the fuze is at ground level or one half inch below. The Type 93 (1933) mine, which is normally used, does not always damage the track of a medium tank sufficiently to disable it. The Japanese, therefore, generally lay one mine on top of another or placebooster charges

Other artillery pieces of larger caliber have also been used by the enemy to counter tank attacks. The 70-mm battalion and 75-mm regimental guns and howitzers have been employed to cover road blocks, antitank obstacles, and minefields. Antiaircraft guns are frequently sited so that they can engage tanks.

5. TANK FIGHTERS.

The Japanese put unusual stree on close quarter attacks against tanks by individuals or small groups, known as "tank fighters". These groups, in most cases, consist of two or three men. The various weapons they have employed include:

- Armor piercing magnetized mines.

- Mines tied to grenades.

- Clusters of grenades.

- Molotov cocktails.

- Pole mines.

Frequently, a group will operate with a combination of these weapons. Two new, one man attack methods have been encountered recently, which ensure that the attacker does not return if his attack is successful. One of these is the "lunge mine" method, in which an armor piercing charge on the end of a pole is used. The attacker waits in hiding and lunges at a tank with his mine when one approaches. The mine explodes on contact. In the other method, a Japanese soldier has explosive charges strapped to his back. When an opportunity occurs he throws himself under a tank, the charges again exploding on contact.

6. LARGE SCALE ANTITANK DEFENSE.

To combat tanks on a large scale, the Japanese have devised what they call an "elstic defense" ( dansei bogyo ) which operates as follows:

At the approach of a tank attack in force, only some 20 percent of available heavy infantry weapons are used from front line positions. With the exception of one squad per platoon, all units fall back 800 to 1,500 yards. The squads remaining on the front line scatter, lay a smoke screen, and attack the tanks with incendiary grenades as they come through the smoke.

Whuile the tanks are meeting this resistance, they come under the fire of all the main Japanese antitank weapons, sited 500 to 800 yards to the rear. Meanwhile, the divisional artillery moves forward to positions which permit direct firing on the tanks, thus supporting the infantry either in defense or in a counterattack.

Japanese sources state that once a tank attack is stopped by this "elastic defense" methods, the hostile forces are pinched off. The Japanese infantry, although scattered, can still offer successful opposition to hostile infantry which might attempt to exploit the advance of tanks.

An official Japanese Army source states: "Tanks must be defeated at all costs". It is apparent that this is the attitude of all Japanese units, and the employment of suicide tactics against tanks will increase until such time as the Japanese higher command increases the number of antitank guns within units. These suicide tactics may include those types of attack already familiar, together with more original methods.

1. BASIC DOCTRINE AND PRACTICE.

The offensive principles that so completely characterized Japanese infantry doctrine have their corollary in artillery tactics. The primary function of Japanese field artillery is conceived as the immediate and close support of infantry assault. speed of maneuver and constant endeavour to achieve surprise, believed essaential in infantry tactics, apply with equal validity to Japanese artillery doctrine. Other important artillery missions are recognized, but in practice the importance given the close support mission has led to incorporation of artillery with infantry to a degree that would be considered excessive in other armies.

Insistence upon the necessity of keeping artillery well forward in support of advancing infantry is almost as strong among Japanese artillery officers as among those of the infantry. Thorough artillery preparation is recognized in theory as a prerequisite for successful infantry attack. Inadequate Japanese artillery preparation can be charged to a confidence in the self sufficient of the infantry, a lack of appreciation of massed fire, the necessity of a considerable prior registration, and, in many instances, a lack of ammunition. Concentrations have been weak both in duration and intensity, and counterbattery has been poor. To a large extent, artillery raiding parties are relied upon to combat hostile artillery. Traditional reliance upon infantry against modern opponents is too ineffective and costly to escape the notice of the Japanese High Command. Efforts are being made to augment fire support in offensive operations, and increasing stress is being laid upon the need for effective counterbattery fire. However, the tactics of the artillery units so far encountered are not up to the theories laid down by the high command.

2. EMPLOYMENT OF ARTILLERY IN THE OFFENSIVE.

a. Artillery with adcanced guard.

Artillery with the advanced guard usually leapfrogs form position to position behind the infantry component. the movement is made simultaneously if the situation permits. Its promary mission is to give close support to the infantry, but it may also be used to interdict or harass enemy columns. In theory, it even may be used for limited counterbattery against wrtillery pieces and to silence heavy machine guns. This artillery is supposed to bring fire on targets at the maximum possible ranges, but in practice the longest range is about 5,500 yards probably because of the diffuculties of visual observation beyond this distance. With the completion of its duties with the advance guard, the artillery unit reverts to the control of the division artillery officer, or to the infantry commander if attached to a unit of that arm. This change of control is to be made in sufficient time for the former advance guard artillery to coordinate effectively in the main attack.

b. Selection of positions.

Another duty of the Japanese advance guard artillery is the selection of positions and observation posts for the unit artillery. Consideration also is given to the location of areas for the unit trains and to routes of advanceand resupply to the positions chosen.

The tactical principles of Japanese artillery dictate the choice of positions certainly located in the rear of the attacking infantry. (An exception to this dictum is made in jungle warfare as is discussed in part II). The positions usually are chosen as far forward as it is possible to obtain the necessary concealment. They are selected to permit the concentration of fire on the area of the main attack, yet to allow a considerable shift in direction of fire if changes in the situation require. Such locations also enable the artillery to give closer and more direct support to the infantry. The favorite location for positions, is a gentle reverse slope, preferably in a wooded area. Alternate positions are selected in advance of whenever this can be done.

If a new position is to be taken, ammunition is stockpiled there is possible, but at all events the ammunition supply is replenished before th emove is made. The Japanese site observation posts well forward and uses the observers boldly, often sending them well ahead of their forward positions and relying on their mobility for their protection. Fire is adjusted from observation posts in a normal manner, using battery commander's scopes, aiming circles range finders, and field glasses. Especially with infantry guns, the observation posts usually are located within voice range of the gun positions.

They are placed as close as possible to the gun target line because the small T method of adjustment apparently is preferred. Air observation has not been used, probably because of lack of air strength rather than because of lack of appreciation of its value as training in its use is given at the artillery school.

Guns are normally sited in single gun positions, though sometimes sections of two guns are emplaced together. When battery positions are used, the guns are sited with one gun behind the other (about 100 to 200 yards apart) down teh gun target line. positions are rarely at right angles to this line. sniping and roving guns are used extensively, though they usually are attached to infantry units. All guns are well dug in and camouflaged. Dummy positions, established in practically all situations, are considered by the Japanese to be one of the most effective defenses against counterbattery fire.

When more than one gun is employed in a single position, the Japanese often mix calibers, so that one 105-mm guns and one 150-mm howitzer may be firing from the same location. Battery firing positions have been known to be arranged in squares. Two guns constitute a section, and the pieces of each section are sited one behind the other. One section fires its guns alternatively at one tartget, while the other section does likewise on another target. These guns may also cover medium artillery registered on the same target and sited in depth down the gun target line.

Japanese artillery communications depend mainly on wire telephone circuits, supplemented by other signal means,except radio which has not been used by the units so far encountered (1944).

c. Fire plans,

Since the Japanese think of artillery as a weapon for direct infantry support, their fires are usually confined to prearranged infantry support tasks. This is evidenced by their ignoring many targets of opportunity upon which heavy casualties and considerable disorganization could have been inflicted. such oversight is explained partly by the Japanese inability to transfer fires rapidly from one target to another and partly because the new targets were not included in the original plan, and had no direct bearing on the immediate operation.

The Japanese seldom have used mass fires nor have they fired cocentrations in the manner of Allied artillery. Until very recent operations in Burma, they had not been known to fire more than six guns at one target at one time. The Japanese apparently conceded the superiority of Allied artillery for they used several passive measures to protect their guns. Fire was delivered at night only when support was required for an infantry attack. Such fire seldom lasted for more than 1 hour and ceased immediately if Allied planes appeared over the area of the gun positions.

Japanese guns usually cease fire during the day or at night if Allied planes are overloaded, but exceptions to this have been noted recently. To avoid detection by Allied sound and flash ranging units the Japanese resort to such countermeasures as firing several calibers from widely separated localities, firung alternatively from two locations during registration, employing small caliber artillery covering fire for medium weapons, simulating sound and flash from positions forward of the true location of the firing pieces, and moving to new positions after each fire mission. Medium artillery often is emplaced so far to the rear as to be beyond the range of Allied light artillery and only within the extreme range of medium weapons.

d. Accuracy and effect of fire.

Although accuracy and effect of their fire are good, in nearly all operations the Japanese have neither concentrated nor massed fires. Instead of guns against a single target in a short period of time, they place fire from a very few guns slowly, though accurately, on the one target. In a recent operation, however, they have shown an ability to concentrate fire from a large number of weapons of all calibers on one target area from widely separated positions.

Ammunitions is not wasted, and the weapons are quite accurate when obeserved fire can be used and sufficient time is available for registration. The zone of dispersion for medium weapons is small; the effect of individual rounds is quite comparable to Allied rounds, and teh fragmentation of shells is good.

e. Artillery in the meeting engagement.

In the meeting engagement, the Japanese artillery is used mainly in the meeting engagement, the Japanese artillery is used mainly in direct support of the infantry. The artillery is attached direclty to the infantry, particularly where the front is wide, liason is diffcult to maintain, the terrain is broken and wooded, or combat begins unexpectedly. Japanese doctrine indicates that ideally the artillery in the meeting engagement should be under the command of the division artillery commander, but this does not seem to be carried out often in practice.

The missions during the deployment for the attack are the same as during advance to contact. Once the attack begins, fire is shifted to hostile infantry reserves, as well as to enemy artillery, though the prime emphasis is on the direct support of the infantry. In the final phase of the assault, the Japanese expect to concentrate their fire in the area of decisive importance and to interdict routes available for the forward movement of enemy reserves.

f. Artillery in the attack of a position.

In the attack of a strongly held position, the Japanese doctrine calls for the reinforcement of the divisional artillery by battalions of light and medium artillery. Almost always, the artillery is assigned direct support missions, none being held in general support. Some of the reinforcing artillery may be used for counterbattery work, but that mission usually is reserved for the artillery under army control.

Some attempt appears to have been made by high Japanese commanders to increase the flexibility with which the guns are employed and to ensure the centralization of command on which modern performance depends. But, in actual operations these two requirements have been almost completely lacking except in the most recent fighting around mandalay and, perhaps, in teh defense of Iwo Jima.

The attack of a position usually is made at night, in which event the artillery completes its registration during the previous day. An attack in daylight occurs, in theory, 1 or 2 hours after dawn which allows the artillery time to register by daylight prior to the attack. The first phase of the attack is aimed at the outpost line, and the larger part of the artillery is placed on the flank where the main effort is to be made.

The remainder is assigned to the area of the holding attack. some of the guns may be given counterbattery missions during this time, although lack of artillery has often forced the total neglect of this mission so far as the guns are concerned. When the outpost line has been taken, the artillery shifts to counterbattery, interdiction, and harrasing fires until the scheduled time for the beginning of the artillery preparation has arrived. The total period usually assigned for firing a preparation is 1 to 2 hours. Of the fire laid down, about one third is devoted to each of these tasks:

1) Ranging.

2) Obstacle destruction and wire cutting.

3) Neutralization fire against enemy infantry positions, including fixed fortifications.

This allows no fire to be brought against the enemy's positions in depth, while teo thirds of the fire is directed against highly unremunerative targets. When the attack begins, the mission of the artillery changes to one of direct support with special attention to the area of the main effort, usually one of both flanks of the enemy position.

The possibility of dawn attacks should increase as the enemy perfects his technique of night survey and more rapid daylight registration. This apparently has received much consideration from Japanese authorities and the possibilities of such attacks are becoming more and more likely, granted sufficient personnel and materiel are available. Observation posts are pushed farther forward, if the guns cannot be moved, to compensate for the difficulties of night observation and registration.

g. Artilleryu in night attacks.

Night attacks in force are distinguished in Japanese doctrine from the more favored night attcks by surprise. Only in attacks in force is there any artillery preparation. The artillery in this type of attack is expected to fire on designated target areas upon infantry rocket signal. Special consideration also is given to fire missions that will limit the enemy's ability to counterattack decisively. The Japanese believe that artillery in support of a night attack should be kept as mobile as possible, and excessive rigidity in formulating fire plans is condemned. This is a particularly strange doctrine because carefuk prior planning is necessary to insure that concentrations are delivered in critical areas and that friendly troops ae not endangered by the bursts. Artillery fire is used in night attacks as an aid to the maintenance of direction.

h. Artillery in the pursuit.

As soon as it is discovered that the enemy is withdrawing the Japanese attach most of the artillery to forward infantry regiments to facilitate coordination and rapid liquidation of enemy covering positions. The general mission of the artillery is to disrupt the enemy's retreat by interdicting junctions and bottlenecks in the road net, bridges, defiles, etc.

As the pursuing infantry penetrates the enemy covering positions, the attached artillery follows it by bounds and, when necessary, concentrates its fire on resisting enemy infantry. Battery commanders are directed to retain the ability to occupy firing positions quickly, and teh line of command is kept as direct as possible. It also is held to be advantageous in pursuit operations to fire on the enemy's flanks wherever possible, and to conduct vigorous reconnaissance in order that successive firing positions will be in readiness as the pursuit continues. Routes of advance to these new positions of course must be prescribed and carefully concealed from the enemy.

i. Critique of Japanese artillery employment in the offensive.

There are many weaknesses in the Japanese artillery technique and employment in the offensive, of which most fundamental is the primitive state of development of the doctrine on which their artillery performance rests. The most obvious results of this faulty doctrine have been:

(1) Lack of massed fires.

(2) The failure to fire on suitable targets.

(3) The mixing of different calibers and types of artillery in a single battery.

(4) The lack of sufficient pieces of all types.

(5) The inordinate length of time required for registration.

(6) The long period required for the transfer of fires.

(7) The lack of a fire derection center.

(8) The absence of technical means of counterbattery intelligence.

(9) Failure to consider countermortar and counterflak fire.

(10) Lack of appreciation of modern methods of planning the use of artillery, both in relation to other arms and in its internal arrangements.

(11) Failure to consider calibration of pieces and the preparation of tables to correct for wear.

(12) onsiderable confusion as to the requirements of neutralization fire. Specifically, the weakness of Japanese artillery in the division makes it unable to carry out the assignments normally given to such a unitif any offensive mission against a modern opponent.

For example, unless the organic artillery is more strongly reinforced than is likely, it does not have the strength to carry out the basic mission of neutralization of the enemy's defenses prior to the attack. No real neutralization of a strongly dug in position can be achieved by divisional artillery that contains three battalions of light and one battalion of medium artillery. Even in a strengthened division, the organic artillery is incapable of furnishing the volume of fire needed in the attack.

Further, the usual dispersion of the pieces of artillery among various infantry commands reduce the efficiency of the artillery and makes it almost inflexible in its operations. However, in the Japanese army, the necessity of a more modern approach to artillery practice is recognized, and each successive operation should find Japanese guns better prepared for offensive assignments.

There seems to be little question but that Japanese artillery will be more effective in the future, particularly in concentrtaion of fire , flexibility of operation, centralization of command, and availability of ammunition. The establishment of a fire direction center is not to be anticipated from any information yet received. In fact, the idea appears strange to all Japanese artillery officers, even those of the highest rank, though it may be that they understand it but feel that the average Japanese artilleryman does not have sufficient training to operate a fire direction center.

3. EMPLOYMENT OF ARTILLERY IN THE DEFENSIVE.

a. Location of positions.

In the defense of a position the Japanese realize the need for artillery support for the defense of the outpost line. A relatively small part of it is placed forward of the main line of resistance; most of it is emplaced behind it. The primary considerations in the siting of the artillery usually are its use as support for the infantry zone resistance through the use of limited normal barrage and concentrations and the development of effective coordination of fire of the two arms. On occasion, the artillery may be sited within the infantry positions, but, if this is done, every precaution os taken to avoid diminishing the fields of fire of the pieces.

Observation posts usually are behind the infantry positions, although observation posts within those areas are used when the situatio requires. Alternate or switch positions are prepared, since normal practice is to shift all pieces after the firing of each mission. The batteries generally are echeloned in depth from 1,700 to 2,200 yards behind the main line of resistance. Positions are chosen to facilitate effective interdiction fire at extreme ranges, but the guns are so sited as to make possible their immediate shift to direct support of the defending infantry without change of position. In an area in which the enemy has a preponderance of artillery, the Japanese may site their medium weapons in considerable depth, beyond the range of all light and much medium artillery of the Allies. This limits the depth of the enemy position that can be brought under fire but effectively prevents counterbattery fire against the Japanese pieces. simulated sound and flash is used to prevent or limit direction of actual pieces.

b. Responsibilities of unit and artillery commanders.

The Japanese division commander on a defensive mission prescribes the direction of fire of the artillery, designates the most vital sectors of the main defense line, and selects in general thet areas in which the artillery is to be emplaced best to support the infantry plan of defense. He also fixes the time at which fire for adjustment will be undertaken, and the time and rate of fire for effect. On receipt of these instructions, the artillery commander issued orders for the deployment of the division artillery and assigns definite missions to the main subordinate units. He also prescribes the type and method of fire which include the locations of areas of concentrations and limited normal barrages, the ammunition to be used, and the priority of targets.

c. Conduct of fire.

On the defense, Japanese tactical doctrine directs that the artillery place its largest volume of fire on the area between the main line of resistance and the defensive positions on the outpost line or on the advance defense position. The greatest concentrations are fired in front of, and subsequently within, the network of infantry fire from the main line of resistance; artillery commanders are told to retain the capability to bring fire within the main battle position as well.

The densest fire is planned in the area through which the main enemy attack is expected to pass. Nevertheless, in addition, considerations is given to siting of the artillery to support counterattacks against likely enemy penetrations of the main battle position.

Japanese defensive artillery first delivers interdiction fire against routes of approach of enemy units and probable assembly areas. This interdiction fire is followed by a limited barrage as the enemy approaches the main line of resistance. From the viewpoint of modern artillery practice it is surprising that relatively few of the available pieces are committed until the enemy is within close range. However, the Japanese feel it better to conceal the strength and position of their artillery than to expose it to counterbattery. Such methods of fire are contrary to accepted principles but also agree with the Japanese emphasis on destruction of the enemy in close combat.

Counterbattery is avoided during this period, and enemy counterbattery is opposed by a frequent shifting of the position of the pieces engaged . The artillery must be prepared to assume an antitank role as conditions require, not only to protect the artillery itself but also to aid the infantry in maintaining their positions against tank attack.

d. Ground units in counterbattery operations.

The limited quantity of Japanese artillery greatly restricts the missions that can be fired by it, and the one usually neglected is counterbattery. The Japanese, however, understand thoroughly the need for destruction of enemy artillery and, since they cannot destroy it by fire, attempt to destroy it by raiding units. These infiltrate through the enemy lines and attempt to reach the actual pieces to render them useless by placing explosive charges on one or more of their vital parts.

Such raiding units often, though not necessarily, are suicidel. Their organizations are quite flexible and are adapted to the types of weapons to be attacked and the terrain to be crossed. Such tactics naturally are more feasible in the jungle than in other types of country.

e. Critique of Japanese artillery employment in the defensive.

In defensive operations so far conducted, Japanese artillery has been poorly used, partly because of a lack of weapons and of ammunition but also because of the fundamental doctrine that govern its use. Fires of all types are delivered far too slowly by an inadequate number of guns and, apparently, with little consideration given to the requirements in ammunition for the reduction or neutralization of the target in question.

The use of survey methods has been difficult in the areas in which the Japanese have been fighting, but even the surveying of the gun positions of a single battery in relation to each other has been neglected. As a result, the adjustment of fire has been done usually by each piece separately. This practice has increased ammunition consumption and has made adjustment particularly difficult when more than one gun was firing on the same target. The tendency to hold artillery in reserve has reduced the potential power of Japanese fire. Althuogh a lack of ammunition and a fear of counterbattery fire have been responsible for this in some instances, a basic bias against a non-firing reserve is usually the cause. Japanese artillery has improved in effectiveness in the most recent operations.

To a large extent this improvement can be explained by an increase in available guns and ammunition, but definite instances of the handling of artillery in a modern manner have been noted and are likely to increase as the Allies come closer to the Japanese home islands.

4. EMPLOYMENT OF ARTILLERY IN DELAYING AND WITHDRAWLS.

In a delaying action, the Japanese artillery takes the enemy under fire at extreme ranges from positions close behind the infantry forming the covering force. In contradistinction to the usual practice, the pieces are grouped closely by battery and battalion for ease in control and direction of fire, for the Japanese believe that the danger pf enemy counterbattery is relatively small in such operations. A portion of the available artillery is kept in reserve at some distance behind the position as the base of fire for the next line of defense. When the delaying forces move back from one delaying position to the next, this artillery has the mission of covering that withdrawal.

In Japanese doctrine, the daylight withdrawal is not looked upon with the disfavor that it finds in other armies, and such an action makes a heavy call on their artillery. The division reserve is usually committed as the covering force, and the division artillery is deployed behind the covering position to aid in protecting the withdrawal. In a night withdrawal, the Japanese do not organize a covering position but instead leave behind a number of small detachments, heavily equipped with automatic weapons to form a covering "shell".

Only a small part of the unit artillery is assigned to the covering "shell", and both the infantry detachments and the artillery are expected to sacrifice themselves, if necessary, to cover the retirement of the main body. Normally, the artillery remains in position until nearly dawn and then is withdrawn to the control of the main body.

5. EMPLOYMENT OF ARTILLERY IN RETREAT.

In a full scale retreat, only a relatively small portion of the Japanese artillery is used with the rear guard; the rest attempts to withdraw along covered rouutes. Such artillery as is employed is placed near the flanks of the retiring force do that it can fire until the pursuer is quite close without endangering the retreating Japanese.

6. EMPLOYMENT OF MORTARS.

The Japanese have exploited thoroughly the capabilities of the mortar, particularly in their jungle operations. For every close support of the infantry they have relied on the 50-mm grenade discharger which they have used with considerable accuracy and effect. However, this weapon does not have the requisite range and effect to provide the needed base of fire for the infantry. Therefore, larger weapons have been used to provide the fire power needed by ground units.

In the attack, mortars are used well forward to neutralize defended localities that are holding up the advance, which cannot be engaged by machine guns, and for which artillery is not available or pehaps even suitable. They also are employed to replace artillery in areas to which even the light Japanese artillery pieces cannot go. The methods of employment of mortars are quite similar to those of most Allied armies, with emphasis on the close support role of the weapons; little consideration is given to their employment in large numbers to provide massed fires. Rather they are used primarily to supplement the other heavy weapons of the infantry unit. The larger mortars are used in the main to provide additional fire power for the unit artillery and are givem missions normally assigned to artillery. They, as well as the artillery, are seldom fired with modern methods of fire control.

In the defense, mortars are employed against probable avenues of approach and against assembly areas. If the forward Japanese positions are overrun but still occupied , mortar fire often is brought down on their own pillboxes and shelters on which the mortars were ranged in advance. Such methods are not likely to injure Japanese troops within the positions and are almost certain to place fire among or near attacking Allied troops. As is true of their artillery, the Japanese usually move their mortars frequently to alternate positions established well in advanced of the need for them.

Japanese methods of mortar fire control are based on the use of an observer (usually an officer) who takes a position close to the gun target line and who estimates ranges with the help of field glasses rather than by the use of any of the more complicated types of range finders. Orders are transmitted by field telephone of, if the observer is close enough, by visual signal. one rather novel method of target indication has been the firing of intersecting streams of tracers over a target that could not be reached or properly engaged by machine guns. The observer then directed mortar fire on the point where the tracers crossed within a few seconds after machine gun fire was opened.

Mortar fire is usually brought down on Allied troops during the firing of an Allied barrage to give the impression that at least some of the pieces are firing short.

The tactical use of both types of Japanese mortar units seems to be much the same, though they may be designed as either infantry or artillery mortar units. In most front line work the mortars are assigned to the direct command of the immediate infantry commander, who is responsible for their employment. However, when large mortars are used, or when they replace all or part of the divisional artillery, they may well be held under the direct control of the artillery commander.

As operations shift from the jungle to more open types of terrain, the Japanese use of mortars to replace and supplement field artillery will be less and less feasible. This is mainly because of the greater displacement in depth that will be required of all arms in areas where concealment is far less available. The shorter range of the majority of Japanese mortars will prohibit their use from positions at any great distance (over 1,000 yards) behind the main battle positions.

1. GENERAL.

Japanese antiaircraft measures are both passive and active. Within the capabilities of their weapons the Japanese have achieved a fair degree of success. Little tactical change has been observed on the island campaigns thus far; the developments noted have been in the nature of improvisations rather than fundamental changes in doctrine. On the Japanese mainland, however, a radical departure from earlier tactics has recently been observed.

In the earlier stages of the war, decentralization in the control of antiaircraft batteries was common. This was probably dictated by shortages of equipment and the desire to achieve a maximum of protection with the materiel available. Six gun units were often subdivided into three two gun batteries.

In a recent observationof an antiaircraft installation in Japan it was noted that a concentration of four individual batteries has been made, but, instead of combining all of the guns into one intrgrated battery defense, individual battery organization was retained. Weapons of different calibers appear to make up this "master" site so that fire control data probably will have to be computed by the individual battery. A gun laying radar is included in this new antiaircraft defense system. This is in addition to a probable searchlight and radar combination. The Japanese, in their defense of vital homeland installations, will be able to deliver a greater concentration of fire by this new battery arrangement with a probable increased efficiency in operational control.

2. MISSIONS OF ANTIAIRCRAFT ARTILLERY.

The primary mission of Japanese antiaircraft artillery is the defense of vital areas and installations against attack by enemy aircraft. In the assignment of priority areas to be defended, the Japanese follow the same tactical consideration which governs the employment of antiaircraft artillery in other armies.

Japanese antiaircraft artillery is often sited so that it can be used in the role of field artillery. This is specially true in the widespread use by the army of navy dual purpose weapons such as the 120-mm and 127-mm dual purpose guns. On Saipan, twin mounted 25-mm guns were found on steel sleds with towing rings for movement from position to position.

3. WARNING SYSTEMS.

In order to obtain an early warning of the approach of hostile aircraft, the Japanese employ the conventional agencies and methods. Radar is generally used in all important defense systems. Some of teh sets are capable of more than 60 miles range, but as a general rule the Japanese have not achieved great proficiency in radar development.

Outposts, employing visual observation, are used extensively to alert guns and searchlights. These have been located on outlyign islands or on such terrain features where they can obtain the earliest warning possible. Readio and telephone are used for communication, and teh observer is generally equipped with binoculars for observation purposes. In other instances, the gun crew act as air guards and endeavor to obtain their own advance notice of impending raids.

As the war approaches the Japanese homeland, there is evidence that warning systems will be more elaborate than previously encountered. In important areas of Japan there appears to be a well organized aircraft early warning system, supplemented by a close coordination of antiaircraftartillery, searchlights, and fighter planes. In one vital area in Japan, information is disseminated, simultaneously, to all defense units, down to and including antiaircraft battery headquarters.

Telephone and wireless communications systems have been installed to expedite early warning which comes from observation posts and radar statons which apparently report into a central defense headquarters.

4. PASSIVE DEFENSE MEASURES.

Passive antiaircraft meaures used by the Japanese include the construction and use of dummy positions and camouflage. By these means and attempt is made to conceal the defended area from aerial observation, to make it appear as a non military objective, or to draw fire of the attacking aircraft. Camouflage encountered, to date, has generally been good as far as the smaller installations have been concerned, but attempts at the concealment of large targets have not been particularly successful.

The Japanese mayu be expected to exploit more fully these attempts at deception, with dummy guns, camouflage, and frequent movement of weapons to alternate positions - this latter measure has already been extensively employed.

5. ACTIVE DEFENSE MEASURES.

a. Weapons.

Antiaircraft weapons of caliber ranging from 6.5-mm light machine gun to the 127-mm (Navy) gun are known to be in use by the Japanese army in their active antiaircraft defense systems. Their high velocity weapons have estimated effective ratings up to 27,000 feet. These weapons are used to destroy attacking aircraft or to cause them to abandon their mission. Ammunition used by the Japanese includes ball, incendiary, and high explosive fragmentation projectiles with powder train and mechanical fuzes.

b. Barrage balloons.

These have been employed as protection against hostile aircraft. When used near water areas, the balloons are usually painted a greenish blue making them difficult to detect. In some localities of Japan proper, barrage balloons have been flown at altitudes ranging uo to 4,000 feet.

c. Night fighter planes.

In conjunction with antiaircraft ground defenses, night fighters have been used but without much success. In one defended area, the zones of the night fighter were limited to areas outside the firing radius of the antiaircraft guns. The artillery ceases fire, however, when the hostile plane is pursued by the Japanese night fighter in the area of gun operations. The night fighters generally patrol on the other fringe of the searchlight ring. There is some evidence that night fighter planes are equipped with radar.

d. Other measures.

The Japanese recently have begun to employ a variety of improvisations to supplement their antiaircraft defense systems. Among these weapons are aerial burst bombs. Such bombs, equipped with impact and time fuzes, can be used against airborne or grounded aircraft. The cluster bomb is one type and is packed 76 bombs to the cluster which opens shortly after leaving the releasing plane. After a drop of a few hundred feet, the individual bombs scatter, with detonation occurring as the separate bombs hit the target.

The air-to-air parachute bomb is another device reported in use. Thi sweapon consists of a small bomb attached to a 150 foot cable. Two small parachutes are attached to the other end of the cable. Antiaircraft striking any portion of teh cable will cause a detonation of the bomb. The cable also presents an incidental propeller fouling hazard.

An innovation in Japanese defense against low flying aircraft is the aerial burst 81-mm mortar shell. While in flight, the projectile is held by a small parachute. The shell explodes when the parachute shrouds are struck or by a self destroying element in the fuze.

The Japanese have begun to use the 75-mm mountain gun as an antiaircraft weapon. Emplaced in such a manner as to allow an increase in elevation, the gun is used against low flying aircraft on strafing or low level missions.

Antistrafing wires and cables have been frequently reported strung across narrow valleys, between trees, and across rivers. This type of obstacle has been suspended from levels between 30 and 100 feet.

The extent of these antiaircraft artillery substitutes can best be illustrated by the reported use of land mines against low flying aircraft. The mine apparently is exploded by a remote control mechanism as the plane passes over the mined area.

e. Train mounted defenses.

The Japanese have mounted antiaircraft weapons on railroad trains in order to furnish protection against low level bombing and strafing. In Burma, one car, mounting four to six machine guns and from two to four 20-mm guns, was attached to railroad trains. in China, antiaircraft artillery has been reported as being carried on teh car immediately behind the locomotive.

6. EMPLACEMENT OF ANTIAIRCRAFT ARTILLERY.

Japanese antiaircraft artillery is usually emplaced within a 1 mile radius of the defended area. The greatest concentration of weapons occurs between the defended area and the sea approaches thereto, along shore lines, and in the direction of enemy territory. Guns are emplaced in single positions, and in batteries of two to twelve weapons. The distance between guns of both heavy and medium companies varies from 40 to 250 feet.